While most hospital discharges are agreed upon by doctors and their patients, there are some circumstances when there is disagreement about whether it’s time for the patient to leave. Most of those disagreements are with the insurance company or another payer who deems that patient’s time is up (and they will no longer pay.) But sometimes the situation is just the opposite. The patient feels as if he or she is ready to leave, but the doctors say no – they don’t believe that the patient is ready to go. If the patient does, indeed, walk out the door, it will be labeled, “Discharge Against Medical Advice (DAMA).”

The first reason is obvious. The longer you stay, the more money they make, as long as they can be reimbursed by your insurance, another payer, or from your own pocket. That time may be limited by your insurer, but the hospital will always do its best to maximize its reimbursement and income from every patient’s stay.

The second reason is less obvious. That is, the longer you stay in the hospital, the more things they can do to you – extra procedures, extra tests and so forth. Of course, the more they do, the more they can bill for. The third reason is relatively new. That is, through the Affordable Care Act, hospitals are penalized if Medicare patients are readmitted within 30 days of their discharge.

So, while their interest may not necessarily be in your improved health for your own sake, it’s definitely important to them that you be healthy enough when you leave so that you won’t have to come back (until day 31 anyway.)

A New York Times article published in early July details the story of Barbara Barg, a Chicago poet, who collapsed at a bus stop this spring. She suffered a heart attack in 2014 and had been feeling vaguely nauseated for several months. She was enroute to see her primary care doctor about nausea when a bystander who saw her falter called 9-1-1. Ms. Barg, 70, didn’t want to go to an emergency room but that was the only place paramedics would take her. “I was freaking out,” she acknowledges.

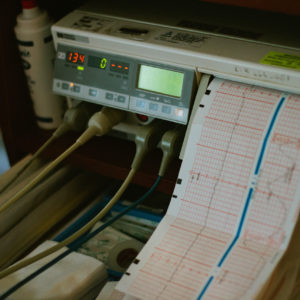

“I’d just gotten out of the hospital, and I didn’t want to go back in.” She’d had two recent hospital stays, one to replace a pacemaker lead, another to look for a blocked artery (none was found).

Now, “I just wanted to see my doctor.” Affiliated with the hospital, he had an office directly across the street. Refusing emergency care, Ms. Barg asked to be taken to his office. No. She asked the staff to call him. No. Twice, she walked out of the emergency department, “and they came after me and said, ‘We can’t let you leave.’”

Finally, after she agreed to sign a DAMA form, an aide wheeled her across the street; her doctor prescribed an anti-nausea drug that quickly resolved the problem.

People discharged against medical advice may be reluctant if problems develop or persist. A study at Highland Hospital in Oakland, California (where most patients were younger) has shown that when they leave against medical advice, they often do not get the appropriate follow-up appointments or medications needed.

“Reasonable people can disagree about whether a patient needs to stay one more day for an additional scan,” said Dr. Cordelia Stearns, a hospitalist, and the lead author. Fuller conversations about why patients want to leave might yield less contentious solutions, including outpatient treatment, home visits or drugs taken orally at home instead of being administered intravenously.